Swept up in events that change the course of history, Polly Sumner becomes a part of that history herself.

1764-1768

”Reading the Stamp Act in King Street, opposite the State House.” Print by James H. Stark (1907)

England asserts the right to tax its American colonies through the Sugar Act in 1764, followed by the Stamp Act (a tax on all forms of paper) in 1765, and the Townshend Acts (a tax on imported glass, lead, paints, paper, and tea) in 1767. The American colonies reject England’s right to tax them, and this causes violent protests and rioting in Boston. The King sends troops to Boston to keep the peace, and one by one, most of the taxes (except for the tax on tea) are repealed. The colonies continue to insist that England has no right to tax them; that only the colonies could levy their own taxes.

1768-1770

Engraving of the Boston Massacre, by Paul Revere (1770)

The continuing dispute over who has the right to levy taxes, and the conflicts between the British troops and the citizens of Boston, leads to more rioting and the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. Samuel Adams blames the British soldiers and plays it up for propaganda value. The soldiers are put on trial, but John Adams successfully defends them as having acted in self defense.

1770-1773

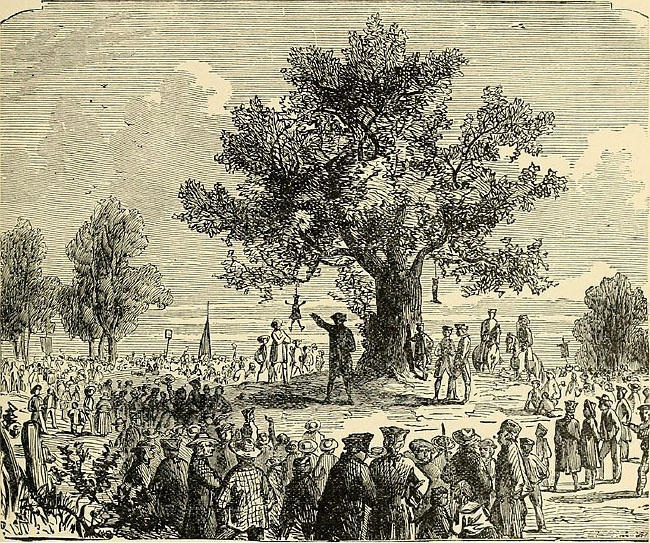

Colonists rallying under the Liberty Tree. From Cassell’s Illustrated History of England (1865)

A period of relative calm. The Sons of Liberty continue to resist British rule and foment political unrest, but only relatively minor incidents occur.

1773

“The Destruction of Tea at Boston Harbor.” Print by N. Currier (1846)

Polly Sumner arrives in Boston aboard one of the tea ships; colonists see the tea shipment as a test of England’s right to tax them, and they dump the tea into the harbor to prevent it from being taxed.

1774

1777 print depicting the British ministry forcing tea and imperial rule down America’s throat. Source: New York Public Library

Parliament passes the Intolerable Acts to make Boston pay for the tea. The port of Boston is closed; more British troops are sent to Boston; martial Law is declared; the Massachusetts Provincial Congress meets in defiance of General Gage and begins to prepare for the possibility of war. Polly Sumner worries that the possibility of war is very real.

April 19, 1775

Minutemen and militia battle the Redcoats in Lincoln on April 19, 1775. Mural by John Rush (1998). Source: Minute Man National Historical Park

General Gage sends British troops to Concord to destroy patriot military supplies. Fighting occurs in Lexington and Concord, and escalates on the British return march through Lincoln and Menotomy (now, Arlington).

June 17, 1775

Bostonians watch the Battle of Bunker Hill from their rooftops. Painting by Howard Pyle (1901)

Provincial troops fortify Breeds Hill, overlooking Boston. The British troops attack and retake the hill but suffer very heavy casualties. Polly Sumner watches the battle from the rooftop of the Auchmuty House in Roxbury. George Washington arrives in July to take command of the Provincial troops, which become the forerunner of the Continental Army.

March 5, 1776

The fortification of Dorchester Heights. Painting by Louis S. Glanzman. Source: National Park Service

George Washington fortifies Dorchester Heights to provoke another battle with the British. The roar of cannons keeps Polly Sumner and others awake for nights. But General Gage decides he can’t afford more heavy losses like those he suffered on Breeds Hill, and he opts to remove his troops from Boston instead of attacking Dorchester Heights. The British troops sail away on March 17, which is still celebrated in Boston as Evacuation Day.

July 4, 1776

The signing of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. Painting by John Trumbull (1818)

The Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, adopts the Declaration of Independence, declaring the Independence of the American colonies from England.

July 18, 1776

Bostonians celebrating the reading of the Declaration of Independence from the balcony of the Old State House. Mural by Charles Hoffbauer (1942)

The Declaration of Independence is read publicly, for the first time in Boston, from the balcony of the Old State House, to a large, enthusiastic crowd. Polly Sumner celebrates along with the others.

1776-1783

Washington crossing the Delaware River on Christmas night, 1776. Painting by Emanuel Leutze (1851)

The War for Independence from Great Britain continues for seven more years before England finally recognizes the independence of the United States of America by agreeing to the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783.

1824-1825

1919

Portrait of Polly Sumner in her current outfit (Photographer and date unknown)

Polly Sumner joins the collection of the Old State House. After having been the cherished playmate of five generations of the Sumner/Williams/Langley family, Polly begins a new career as a museum artifact teaching young people about our common history and founding values as a nation.